The changing styles

of aerobatics

Aerobatics is not a

stagnant sport. The rules evolve and change. The aircraft

available change also, more power, more roll rate - more of

everything. New pilots also come along with new ideas. While the

core figures and elements may not change a whole lot, the

combinations of them and where they are placed in the sequence

definitely change.

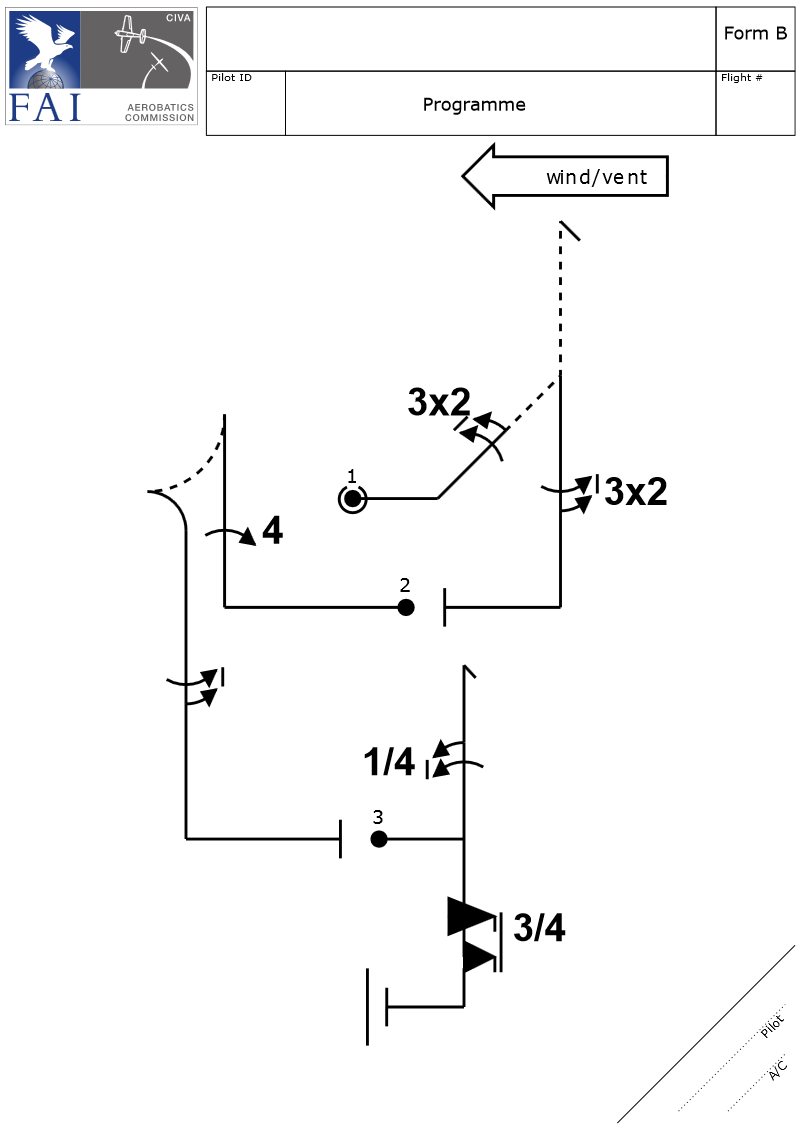

Fig.1

Unlimited Frees from

the 70’s (Fig.1 Zlin 526) and early 80’s (Fig.2 Henry

Haigh, Haigh Superstar 1988 Free) look like extended

Intermediate sequences to today’s eyes.

Fig.2

The number of figures

allowed in the Free was reduced to 9 sometime after this, and

sequences from the early 90’s are quite similar to today. In the

late 90’s a bonus point system was introduced for Frees with fewer

than 9 figures. This led to amazingly complex 7 figure Frees that

were very busy to fly, and also made rational judging a superhuman

task. (Fig.3 Cassidy Free 1999, CAP-222).

Fig.3

This experiment was

dropped and the 9 figure Unlimited Free returned. This does not

mean change has stopped, however (Fig.4 Mamistov Free 2008, Su-26M3).

Fig.4

A smart sequences with

an even spread of K and designed to minimize losses. One exception

would be the use of a full 4-roll rolling circle. It is difficult

to get a good score on any roller, so usual practice would be to use

the lowest K roller possible, and place it late in the sequence so as

not to colour the judges’ opinion of other figures. Mamistov’s

later 2011 and 2013 sequences did change the roller for a simpler

one, influenced no doubt by the 2010 increase in K for all rollers.

Similar comments may be made about the super-eight figure – lots

of steady looping segments and 45’s with rolls to be centred. The

figure is slow flying and allows judges to nit pick many elements, so

hard to score well with. On the other hand it is a relatively easy

figure to practice and refine to perfection, as Mamistov, twice

powered world champion, obviously does.

Often recommended when

designing a Free is to start with a killer figure at VNE and zoom to

the moon – and this is the usual practice today. It conforms with

the traditional approach of starting with lots of energy, assuming

you will have less as you progress through the sequence (Fig.5 Le Vot

WAC 2013 Free).

Fig.5

But this doesn’t suit

everyone, particularly if you are ‘slow starter’ and take a

figure or two to settle and get into the groove. If this is you, it

may be better to start with a technically simpler figure and build

through the flight (Fig.6 Cooper Free WAC 2013).

Fig.6

Supporting this

‘cautious’ approach is the fact you don’t get any chance to

practice your start in the Free Programme – just the safeties and

then straight into it. You should also consider that at a large

International comp you may have to wait days between the Known and

the Free – how current and fresh will you feel when your 15 minutes

of fame comes?

That said, I think you

can see a definite shift in Free design (the exception that proves

the rule?). Possibly this latest move can be attributed to Renaud

Ecalle and his Free of 2010 (Fig.7).

Fig.7

The horizontal start

figure, able to be flown at the bottom of the box, is the defining

characteristic of the new design style. Then the sequence climbs up

for the spin and tailslide, and back down to finish with a minimalist

roller at the bottom of the box. Maintaining energy throughout the

sequence is not the concern it once was. These types of figures are

also appearing more often elsewhere in sequences. Here is another

start figure (Fig.8):

Fig.8

Accuracy and confidence

are needed to make these explosive starts work for you (and no little

amount of skill). Only 4 of the 57 Frees at the last WAC began with

similar low rolling figures. Notable proponents were Holland,

Thomas and Boerbon (2nd, 4th and 8th in the

Free, respectively, USA). It doesn’t suit everyone, and it needs

to be executed flawlessly. Maybe it is a risk that needs to be

taken only if you are gunning for the World Title?

1 comment:

nice info!

br,

inklusi

Post a Comment